Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is caused by malignant transformation of the hematopoietic stem cells. It is predominantly seen in individuals between the ages of 50 and 60 years and is characterized by the arrest of leukocyte development in the early stage of development. Diagnosis is based on the presence of blast cells in the peripheral circulation. AML is treated by chemotherapy, which includes treatment of remission and post-induction remission. Refractory cases of AML are treated by bone marrow transplants. Complications of AML include anemia, infections, and bleeding as well as acute medical emergencies such as necrotizing enterocolitis, hyperleukocytosis, and tumor lysis syndrome.

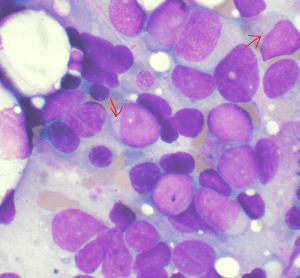

Image: “Myeloblasts with Auer rods seen in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).” by Paulo Henrique Orlandi Mourao. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Definition of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

What is Acute Myeloid Leukemia?

AML is a malignant disease caused by transformation of the stem cells present in the bone marrow. It is characterized by the developmental arrest of malignant cells in their primitive stage.

Epidemiology & Etiology of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Higher Prevalence of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Males

AML is more common in men than women and usually affects individuals above the age of 65 years.

Risk Factors in the Development of AML

- Hereditary causes

- Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome)

- Defective DNA repair (Bloom syndrome, Fanconi anemia, ataxia-telangiectasia)

- Myeloproliferative syndromes (polycythemia vera, essential thrombocytosis)

- Exposure to ionizing radiation (nuclear fallout) involving an extremely high dose of radiation

- Exposure to chemicals such as benzene, commonly used in chemical industries

- Drugs (chemotherapy drugs are the leading cause of drug-induced AML)

- Alkylating agent (busulfan)

- Topoisomerase inhibitors

Age-Based Presentation of leukemia

Presenting factors include:

- Age 40—60 years: myeloid leukemia (AML & CML)

- Age 0 —14 years: acute lymphocytic leukemia

- Age 60 years and older: chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Classification of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

The FAB and the WHO Classification of AML

AML is classified according to the following standards:

- French-American-British (FAB) classification

- World Health Organization (WHO) classification

WHO Classification of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities

- AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22)

- AML with inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22)

- Acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17)(q22;q12)

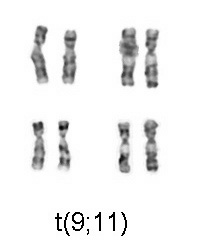

- AML with t(9;11)(p22;q23)

- AML with t(6;9)(p23;q34)

- AML with inv(3)(q21q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21;q26.2)

- AML (megakaryoblastic) with t(1;22)(p13;q13)

- AML with mutated NPM1

- AML with mutated CEBPA

- AML with myelodysplasia-related features

- Therapy-related AML and MDS

- AML with minimal differentiation

- AML without maturation

- AML with maturation

- Acute myelomonocytic leukemia

- Acute monoblastic/acute monocytic leukemia

- Acute erythroid leukemia (erythroid/myeloid and pure erythroleukemia variants)

- Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia

- Acute basophilic leukemia

- Acute panmyelosis with myelofibrosis

- Myeloid sarcoma

- Myeloid proliferations related to Down syndrome

- Transient abnormal myelopoiesis

- Myeloid leukemia associated with Down syndrome

- Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm

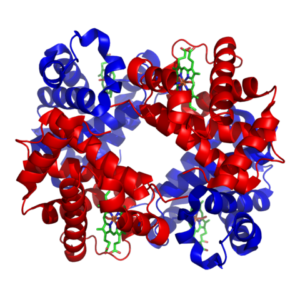

Pathophysiology of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

AML on a Cellular Level

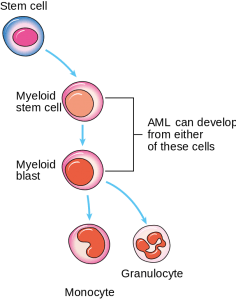

Image: “Diagram showing the cells in which AML starts.” by Cancer Research UK. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

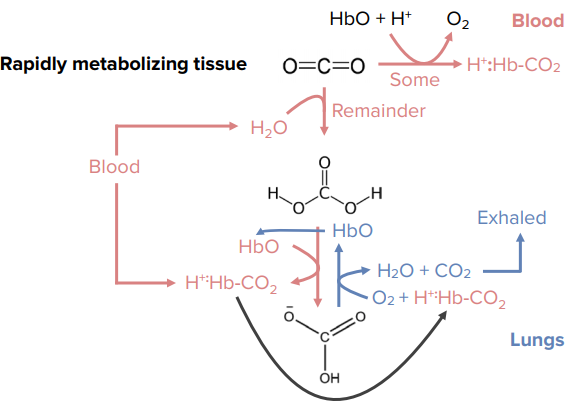

AML arises from the stem cells of the hematopoietic system, which give rise to monoclonal proliferation and replace normal bone marrow cells.

In the earlier stages of AML, there is developmental blockage of the myeloid cells; in CML, this blockage occurs in a later stage. These immature myeloid cells (blast cells) are present in the bone marrow and enter the peripheral circulation. A minimum of 20% of blast cells is required for the condition to be diagnosed as AML. These blast cells can fill the entire bone marrow and may result in dry tap and myelofibrosis.

Image: “Chromosomal translocation (9;11), associated with AML” by Cohesion. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Pathogenesis of AML

Chromosomal mutations can also result in the development of AML. Translocation of t(15:17 ) causes acute promyelocytic leukemia. This results in a fusion of the retinoic acid receptor on chromosome 17 with a PML gene on chromosome 15. The fusion product blocks the maturation in the promyelocytic stage, resulting in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Administration of retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia can overcome this block and can be used in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia.

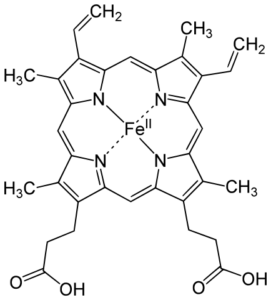

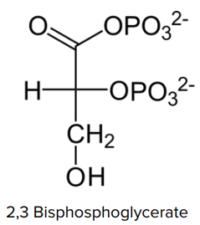

Pathognomonic of AML

Intracytoplasmic rods are seen in the myeloblasts. They have the following characteristics:

- Composed of abnormal lysosomes

- Stain with Sudan Black b stain

- Myeloperoxidase positive

Histochemistry

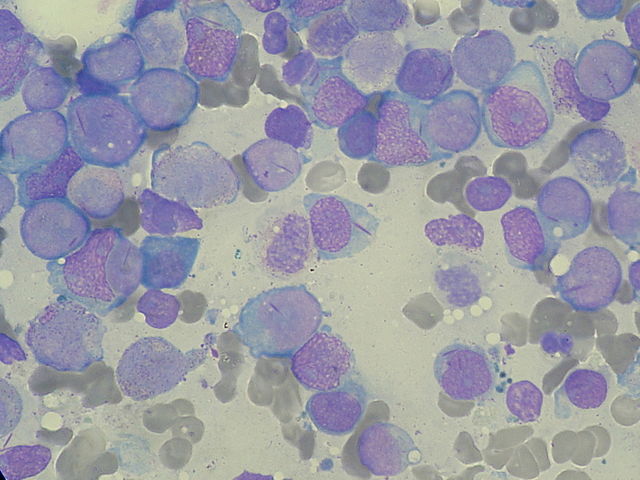

Image: “Bone marrow aspirate showing acute myeloid leukemia. Several blasts have Auer rods.” by VashiDonsk. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Myeloperoxidase positivity indicates the presence of granulocyte differentiation. Auer rods are typically positive for myeloperoxidase. Non-specific esterase positivity indicates the presence of monocyte differentiation.

Immunochemistry

This will indicate the presence of myeloid differentiation markers CD13, CD14, CD15, and CD64.

Clinical Examination and Symptoms of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

How to Recognize AML

Physical examination findings for AML include increased oozing of blood from the intravenous line and ecchymosis. This finding indicates the presence of disseminated intravascular coagulation, in which there is a consumption of all the coagulation factors necessary for the arrest of bleeding. The presence of papilledema, retinal infiltrates, and cranial nerve palsy indicate the presence of central nervous system involvement. Monocytic leukemia most commonly presents with gum hypertrophy and skin nodule formation. The presence of back pain indicates sarcomatous changes in the spine.

Pancytopenia

Pancytopenia is the most significant cause of most AML symptoms, including general weakness and increased infections and episodes of bleeding, especially from the gums and epistaxis. Increased fatigue and weakness are attributed to anemia and usually precede AML. Bone pain in AML is due to the expansion of the medullary cavity in both the upper and lower extremities.

Fever

Fever should be thoroughly evaluated as it is most commonly due to neutropenia. Treatment with broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics is warranted, especially if the neutrophils count is < 1000.

Skin

Findings in the skin include the presence of petechiae ecchymosis due to thrombocytopenia and pallor due to anemia. These can result in leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Eyes

Pale conjunctiva due to the presence of anemia and fundus examination indicates the presence of hemorrhages.

Central Nervous System

Complaints of headache and cranial nerve palsies indicate central nervous system (CNS) involvement; acute monocytic and myelomonocytic leukemia have a greater predisposition for the development of CNS manifestations. Marked elevations of LDH are also seen in CNS involvement.

Oropharynx

Monocytic subtypes typically show the presence of gingival hypertrophy.

Image: “Gingivial Hypertrophy in AML” by Lesion. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Organomegaly

Lymphadenopathy is rare in AML. It is characterized by the absence of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. Their involvement suggests the origin of AML as a result of a complication of a preexisting myeloproliferative disorder. This may be due to the development of blast crisis in acute lymphoid leukemia.

Joint Pain

Joint pain occurs due to the presence of increased deposition of uric acid in the joints, resulting in gout. There is also a possibility of joint synovial infiltration by the neoplastic cells, resulting in joint pain.

Diagnosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Lab Results for AML

Laboratory findings include the following:

- WBC count ranging from 10,000 cells/mm3 to 100,000 cells/mm3 along with the presence of blast cells

- Anemia: Usually normocytic or macrocytic in the presence of a folic acid deficiency

- Thrombocytopenia

- Bone marrow findings show the presence of blast cells. A finding of dry tap indicates extensive fibrosis or hypercellular bone marrow.

The diagnosis of AML can be presumed through a finding of leukemic blast cells in the peripheral smear. Definitive diagnosis is based on the presence of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Immunophenotypic, morphologic, and cytogenetic studies are required for the subclassification of AML and for accurate treatment.

The following two criteria are required for an accurate diagnosis:

- A minimum of 20% blast cells in the bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood. Exceptions include t(8;21), t(15;17), and inv(16).

- Documentation of the myeloid origin, which can be confirmed by the presence of the following:

- Auer rods

- MPO positivity

- Myeloid markers

Therapy of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Possible Treatments for AML

Remission induction therapy includes an initial course of intensive chemotherapy aimed at complete remission of AML. This is followed by post-induction chemotherapy. Younger adults will have better survival rates than those who are older. Older adults are also more likely to have chemotherapy complications compared with their younger counterparts. A bone marrow transplant is used in resistant cases and on a case-by-case basis.

Treatment of Younger Patients

Remission induction therapy regimens for acute myeloid leukemia include the following:

- Regimen 1: cytarabine plus daunorubicin.

- Standard 7+3 regimen—administration of cytarabine for the first 7 days and daunorubicin for the first 3 days (daunorubicin is discontinued after the first 3 days). This therapy achieves 60—80% remission with minimal toxicity.

- Regimen 2—administration of cytarabine plus idarubicin. Dosing schedule for cytarabine includes twice-daily dose for 12 doses along with idarubicin.

Idarubicin is administered immediately following idarubicin on the first 3 days. This regimen achieves a 90% remission rate but has substantial toxicity. Cytarabine and idarubicin show higher rates of remission compared with cytarabine and daunorubicin.

Treatment of Older Patients

Induction chemotherapy is performed with anthracycline and cytarabine; this differs from other chemotherapy regimens.

Post-induction Chemotherapy

This therapy is based on pretreatment cytogenetics and molecular genetics. Favorable cytogenetics for post-induction chemotherapy include t(8:21) and inv(16). For patients with intermittent cytogenetics, treatment includes chemotherapy or bone marrow transplant. Treatment options are based on a case-by-case basis.

Hematopoietic bone marrow transplant is the choice of treatment in refractory cases. Monitoring during therapy is done via regular complete blood counts and renal function tests. Liver function tests are performed weekly. Constant monitoring of uric acid, calcium, and phosphorus are required until they return to normal levels.

Complications of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Bleeding and Anemia alongside AML

The most common complications associated with AML include anemia, infection, and bleeding. The presence of neutropenic enterocolitis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), hyperleukocytosis, and tumor lysis syndrome are considered to be medical emergencies.

Anemia

Anemia is primarily normocytic normochromic anemia, which typically increases on induction chemotherapy. It should be managed with recurrent blood transfusions.

Infection

The presence of neutropenia predisposes patients to recurrent infections, which can be managed with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Bleeding

Bleeding is present due to decreased platelet counts or to DIC. DIC is predominantly seen in acute promyelocytic leukemia (M3). It is characterized by rapid depletion of coagulation factors and results in increased bleeding episodes. Treatment with platelet transfusions is indicated.

Hyperleukocytosis

Hyperleukocytosis is considered to be a medical emergency and is indicated by the presence of increased total white blood cell count greater than 50 x109/L. It presents with symptoms of respiratory and neurological distress.

Tumor Lysis Syndrome

It is considered to be a medical emergency. It presents with acute renal failure due to massive tumor lysis. There is a significant release of potassium, uric acid, and phosphates into the systemic circulation. These obstruct the renal tubules, resulting in acute anuric renal failure.

A minimum of two criteria must be present in order to diagnose tumor lysis syndrome: increased uric acid, potassium, and phosphorus levels; and decreased calcium levels (as shown in the table). These can be prevented by prophylactic hydration and urinary alkalinization. Allopurinol and rasburicase can be used based on risk factors.

Neutropenic enterocolitis should be considered when the absolute neutropenia count is < 500/microL. It is usually diagnosed following chemotherapy. The clinical presentation involves lower quadrant abdominal pain associated with distension. Treatment involves providing supportive measures.

Prognosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Survival Rate

Higher Chances for Younger AML-Patients

Factors that predict a favorable outcome in AML include a younger age of presentation with no previous history of chemotherapy or other hematological disorders.

The following table lists risk factors for the outcome in adults with acute myeloid leukemia:

Review Questions

The correct answers can be found below the references.

1. Acute myeloid leukemia is a malignant transformation of hematopoietic stem cells. It usually affects the individuals above which age?

- 65 years

- 45 years

- 25 years

- 15 years

- 10 years

2. Which one of the following is the pathognomonic of acute myeloid leukemia?

- Nissl bodies

- Neurofibrillary tangles

- Howell-Jolly bodies

- Heinz bodies

- Auer rods

3. For the accurate diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia, what is the minimum percentage of blast cells required in bone marrow or peripheral blood?

- 20 %

- 10 %

- 5 %

- 25 %

- 1 %